Valentine’s Day is a complicated holiday, particularly in adolescence. While children’s experiences of Valentine’s Day are often nostalgically-remembered iterations of the holiday with classroom parties where everyone got valentines, for teens the expectation pivots to the high-stakes hope of a meaningful gift from a special someone, worrying about whether they’ll be chosen or left out, and working to find one’s place in the uncertain landscape of high school relationships, binary gender expectations, and heterosexual romance.

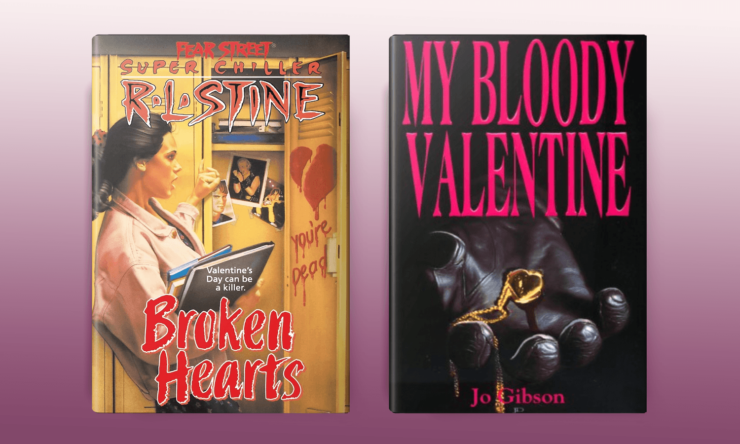

While popularity, the “right” clothes, and who’s dating who are presented as perennial teen problems in ‘90s teen horror, these all seem to hit a fever pitch with Valentine’s Day, with its prescribed romantic rituals, from valentine cards to flowers, dates, and dances. In both R.L. Stine’s Fear Street Super Chiller Broken Hearts (1993) and Jo Gibson’s My Bloody Valentine (1995), these worries are further compounded by mystery, revenge, and murder.

In both of these novels, the young female protagonists receive menacing valentine rhymes, a perversion of both the light-hearted cards of their childhoods and the romantic sentiments they expect to find. The main female protagonists in Broken Hearts are a trio of sisters (Josie, Rachel, and Erica) and their friend Melissa. Josie is the first of the girls to receive a threatening valentine, which reads:

Violets are blue,

Roses are red.

On Valentine’s Day

Josie will be dead. (30)

After sending several more threatening valentines, the murderer delivers on this promise, murdering Josie, and when the horror starts again a year later, Melissa receives a similar rhyme:

Flowers mean funerals

Flowers mean death.

On Valentine’s Day

You’ll take your last breath. (160)

The rhymes here are simple, brutal, and threatening. However, the teens are initially dismissive, writing the cards off as a tasteless prank or the vengeance of an ex-boyfriend, which speaks volumes about the unsettling expectations of relationship dynamics, breakups, and the omnipresent potential of danger or even violence. In Broken Hearts, even one of the “nice” guys is so overcome by rage that he stabs a letter opener into the top of a desk, a problem the young woman he has threatened solves by sliding some papers over to cover up the gouged wood, as through ignoring the damage will erase the experience of her terror. There’s speculation that if a guy would go to all that trouble with the valentines to get a girl’s attention, he must really like her, with the toxic effects of obsession, stalking, or relationship violence completely unaddressed. While the legitimacy of these threats is borne out when Josie is murdered and her sister Erica is stabbed, no one takes Melissa seriously when she starts to receive similar valentines as the one-year anniversary of Josie’s death looms.

The combination of the nostalgic poetic form of the valentine rhymes, the sense of violence as an almost expected part of dating, and everyone’s refusal to take these threats seriously conceals the reality of this danger until it is too late for Josie and nearly too late for Melissa as well. This dual discourse—that the scary valentines are probably really not that big of a deal, but even if they are, relationships are inherently dangerous, so what can you do about it anyway?—bolstered a worldview that is all too common in ‘90s teen horror, in which these young women are always in danger and they can never really hope for safety, but rather must settle for trying to identify the threat before it’s too late. The message to teen girl readers here is that the world is a dangerous place, there’s a good chance they’re going to get attacked, and all they can really do is do their best not to die, all while fending off others’ doubt and accusations that they’re hysterical or overreacting. This is not a worldview that values or believes young women, whether this means the protagonists within these novels or the girls who read them.

The valentine poems in My Bloody Valentine start out with a bit more of a benign tone, though their behavior policing and insistence on a certain ideal of femininity are damaging in their own right. As the young women compete to be voted Valentine Queen, their anonymous poet instructs them that:

Roses are red, violets are blue.

A queen should be kind, faithful and true. (34)

As the bodies and the valentines begin piling up, it quickly becomes clear that the sender is punishing those women who don’t live up to the ideal he has set for them, subjectively determining their “worth” and whether or not they deserve to live. He watches them, tests them, and when he finds them wanting, he kills them, warning them with the final valentine rhyme that:

Violets are blue, roses are red.

An unworthy queen is better off dead. (35)

He places a half-heart necklace around the neck of each of the murdered girls, which bookends this punishment with valentine iconography of cards at the beginning and jewelery at the fatal end. The protagonist, Amy, is the only girl the killer deems to be “kind, faithful and true” enough to live and while most of the novel focuses on the perspective of Amy and her peer group, Gibson intersperses this with with sections told from the murderer’s point of view as he watches and judges the young women he kills, echoing the slasher film tradition of aligning the camera’s point of view with the slasher himself.

In an interesting variation on the traditional Valentine’s Day drama of heterosexual romance, both of these novels feature a range of non-romantic relationships that are actually at the heart of the conflict and violence that drives these narratives. In Broken Hearts, love has nothing to do with the murders, despite the red herring of some boyfriend swapping and the resulting jealousies. Instead, it was Josie’s sister Erica who murdered her, though the threatening valentines actually were sent by Josie’s ex-boyfriend Dave, lending credence to the “it’s a prank, not a death threat” dismissal. Erica’s murderous rage stems from the fact that Josie left Erica alone to care for their sister Rachel, who suffered a head injury and needs constant supervision. While Josie runs around with her boyfriend and leaves the house for hours on end, ignoring Erica’s pleas for help, Erica misses auditions for the school play, is isolated from her friends, and basically becomes a full-time caretaker to Rachel. (Like most of the ‘90s teen horror novels, their parents are largely absent and ineffectual). Erica decides that Josie needs to be punished for ignoring Rachel and after murdering Josie, Erica stabs herself to throw any suspicion onto the jealous ex-boyfriend, which people accept with very few questions or objections (remember: dating is scary and dangerous).

Buy the Book

Dreams Bigger Than Heartbreak

This is further complicated when Erica begins wearing a long red wig while she commits murders the following year, which leads witnesses to believe that it’s actually her sister Rachel that they have seen. Erica tells Melissa “I wanted Rachel to be here too. In some way, she’s here with me, getting her revenge on you” (213). But a much less charitable reading of the situation could be that Erica hopes—whether consciously or not—that Rachel will be held responsible for these crimes and institutionalized, allowing Erica to finally get on with a “normal” life.

Similarly, the driving force in My Bloody Valentine is not romantic love but the connection between siblings, as Kevin tries to exact vengeance on the girls he blames for the death of his sister Karen, who was killed in a car accident after being bullied by several of her peers. Gibson foregrounds the damaging, limited view of ideal femininity early and often in the novel, noting in the opening chapter that Colleen doesn’t wear her glasses “because one of the guys had told her that she looked much better without them” (5) and Harvard-bound Gail plays down her intelligence in order to be more appealing to boys. While Karen herself remains an absent presence throughout the novel, these representations of and interactions between the girls provide a context for these friendship dynamics and how Karen may well have been treated by her peers. As the competition heats up for Valentine Queen, the girls begin to turn on one another, with their interactions driven by pride, pettiness, and casual cruelty, echoing the girls’ earlier unkindness toward Karen. Each of these young women is in favor of calling off the contest for safety’s sake … until she herself is in the lead, when canceling the contest suddenly seems like an overreaction fueled by the jealousy of her so-called “friends.” When “good girl” Amy is the last queen candidate standing and she wants to call off the competition, her friends still encourage her to see it through because the voting is a fundraiser for the library and “we really need more science books” (157), which raises some serious questions about both the state of public school funding and teenagers’ common sense.

For the teens of Broken Hearts and My Bloody Valentine, Valentine’s Day is a horror: romantic love is largely a sham, especially when your boyfriend dumps you and starts going out with your best friend. Relationships are exciting, but also carry the omnipresent potential for violence. My Bloody Valentine’s Danny is the only guy who actually has meaningful conversations with the girl he likes and explicitly addresses issues of pleasure and consent, but he’s also the “bad boy” that no one approves of. A stalker or potential murderer can get away with a lot and evade a good deal of suspicion by hiding behind the guise of a “secret admirer” or anonymous valentine suitor, blurring the lines between mysterious romance and legitimate threat. Even non-romantic relationships are problematic and deadly, with friends and siblings just as dangerous – if not more so – than a creepy ex-boyfriend. In the end, it would really be safer for a girl to be her own valentine or ignore the romantic charade of Valentine’s Day altogether, but that’s never depicted as a legitimate option in Stine, Gibson, or the range of ‘90s teen horror: the only girls without a Valentine’s date are those seen as losers, loners, the unattractive, or the undesirable. Girls who—within this worldview anyway—don’t matter and who are invariably miserable. The only way to be valued is to be desired, but to be desired one must be ready to face the threat of violence and potential death, where Valentine’s flowers could double as a funeral arrangement.

Alissa Burger is an associate professor at Culver-Stockton College in Canton, Missouri. She writes about horror, queer representation in literature and popular culture, graphic novels, and Stephen King. She loves yoga, cats, and cheese.